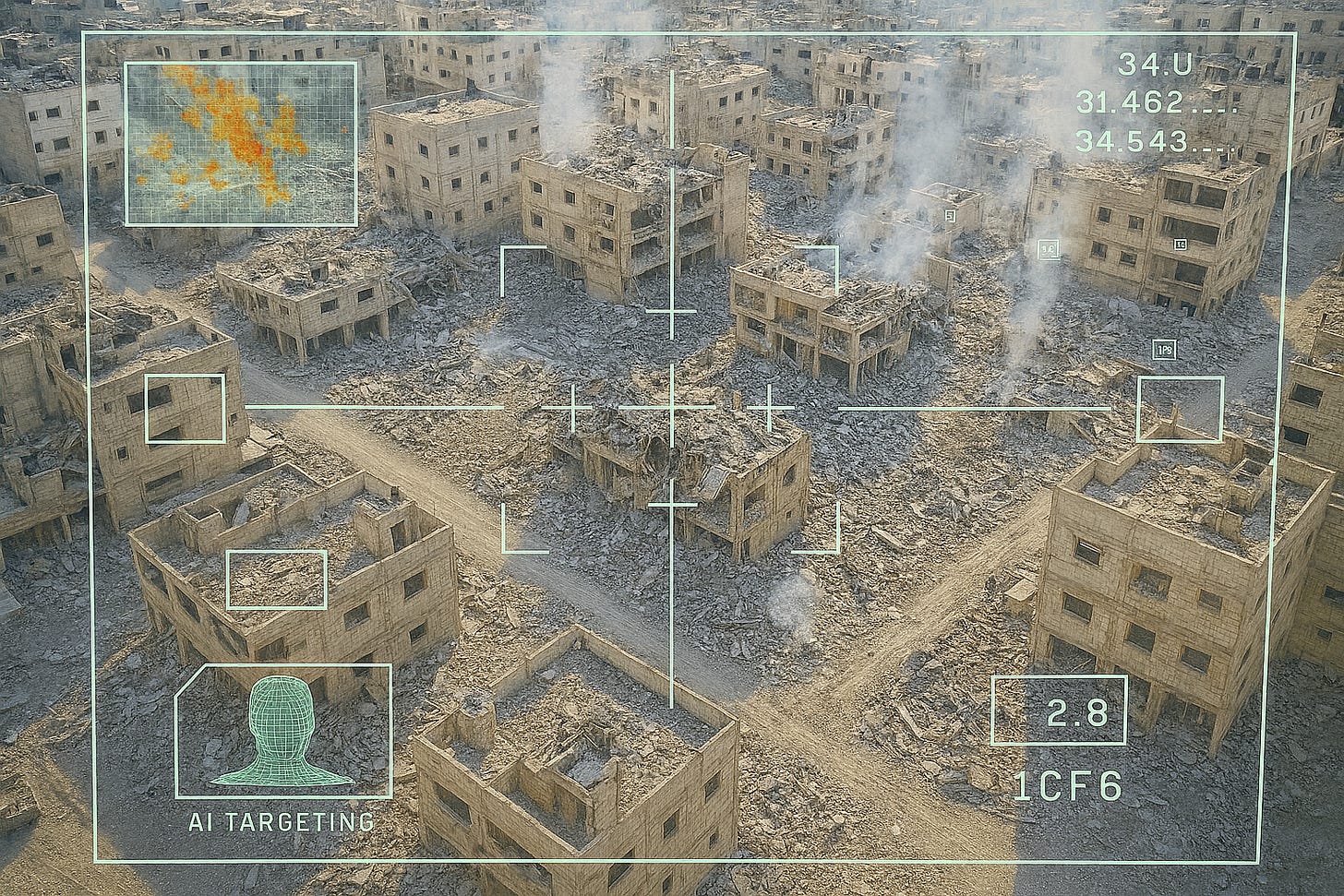

Israel’s AI Systems Have Designed an Industrial-Scale Killing Machine

How to design industrial genocide in the 2020s

Israel’s war on Gaza has revealed a chilling evolution in the use of artificial intelligence in warfare. Behind the devastation lies a network of military algorithms, chief among them ‘Lavender’ and ‘Gospel’, developed by Israel’s elite cyber-intelligence arm, Unit 8200. These systems, known as a are invisible, fast, and built for mass-scale targeting.

I…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Crustian Daily to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.